As we at the Bruce Springsteen Archives & Center for American Music at Monmouth University embark on nearly a week’s worth of events celebrating the 50th anniversary of Bruce Springsteen’s landmark 1975 release, Born to Run, we want to take a moment to reflect on the album’s significance – not just to Springsteen’s trajectory, but also as a primary source document teaching listeners about the time period in which it was created.

A Turning Point

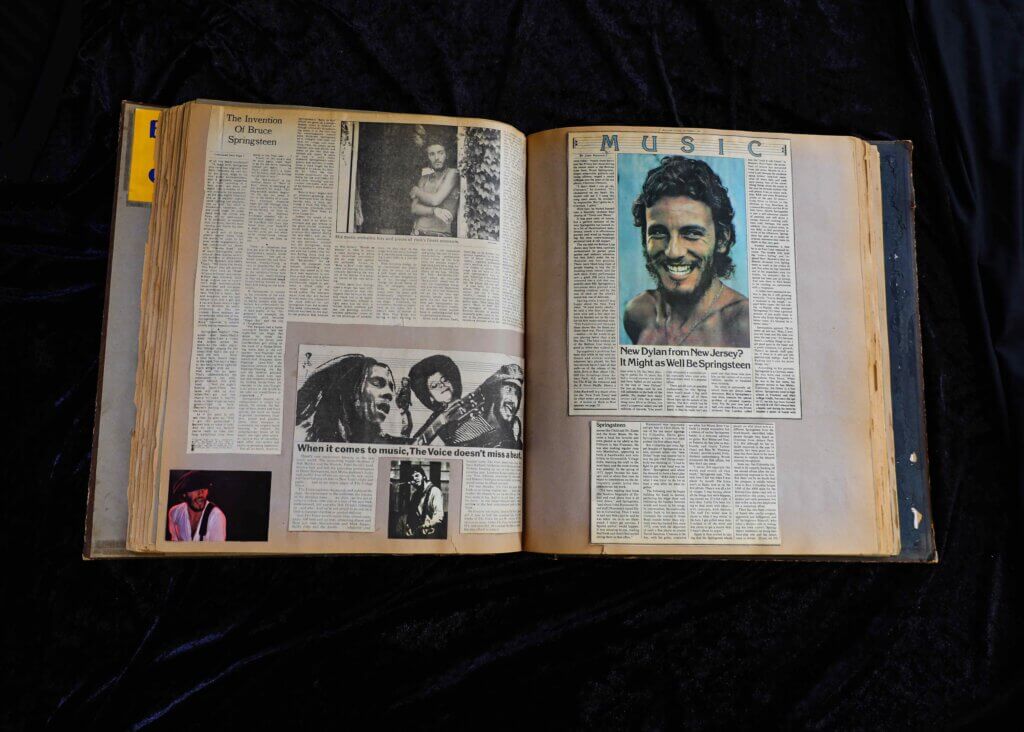

Born to Run is widely regarded as the album that saved Springsteen’s career and established him as one of the defining voices of American music. Before its release, the future of Bruce’s career was uncertain. Though he had been hailed by Columbia Records as a promising new talent and touted (much to his discomfort) by critics as a potential successor to Bob Dylan, his first two albums, Greetings from Asbury Park, NJ (1973) and The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle (1973), had failed to achieve significant commercial success. Critics admired his lyricism and impassioned live performances, but record sales underwhelmed. Perhaps the albums were simply too rooted in Jersey Shore life and culture to resonate nationally (this may also be why, lifelong Jersey Shore girl that I am, they are my favorite – but I digress). The record company also did relatively little to promote them. By 1974, Springsteen faced the very real possibility of being dropped from his label if his next release did not have wider commercial appeal.

Recognizing the stakes, Springsteen hunkered down in a rented cottage in Long Branch – the subject of our new exhibit, Springsteen in Long Branch – and poured everything he had into Born to Run. He wanted to create not just a collection of radio-friendly songs, but a record that felt like a cinematic experience – an album that captured the yearning, frustration, and determination of young people chasing dreams while confronting limitations. His ambition was reflected in the painstaking process of recording. The title track alone took months to perfect, with Springsteen obsessing over every detail of the sound. [See Peter Ames Carlin, Tonight in Jungleland: The Making of Born to Run (2025).]

The result was an album that electrified both critics and audiences. When Born to Run was released on August 25, 1975, it immediately set Springsteen apart from his peers. The title track, with its sweeping scope and rousing chorus, became a rallying cry for restless youth. Songs like “Thunder Road” and “Jungleland” showcased Bruce’s ability to tell deeply personal stories that were simultaneously universal, weaving narratives of struggle, love, and escape into epic rock ballads. The album’s themes resonated strongly in a decade marked by economic uncertainty and cultural shifts, offering a raw combination of both realism and, perhaps somewhat idealistically in spite of it all – hope.

Crucially, Born to Run bridged the gap between critical acclaim and mainstream popularity. Rolling Stone magazine declared it a masterpiece, and Time and Newsweek both featured Springsteen on their covers in the same week the October after the album release – a rare honor that underscored the magnitude of the album’s impact. More importantly, sales caught up to the early hype that had made Springsteen so nervous. The record broke into the Top 10 on the Billboard charts, securing Bruce’s place in the rock pantheon and convincing Columbia that he was worth continued investment.

Without the success of Born to Run, Springsteen’s career could easily have stalled. Instead, the album solidified his reputation as an artist capable of creating music with both gravitas and mass appeal. It gave him the freedom to continue evolving, leading to later triumphs such as Born in the USA. [See more on Springsteen’s catalog in Kenneth Womack and Kenneth Campbell, Bruce Songs: The Music of Bruce Springsteen, Album-by-Album, Song-by-Song (2024).]

In retrospect, Born to Run was not only the album that saved Bruce’s career, but also the one that defined his enduring identity: the voice of the American everyman, chronicling the struggles and dreams of ordinary lives with extraordinary power.

A Reflection of Its Time

As a longtime history professor, I’m always keen to point out that Born to Run is not only a landmark in the life and career of Bruce Springsteen, but also a historical reflection of the United States during the mid-1970s. It was an era marked by turbulence. The optimism of the 1960s counterculture had faded, replaced by the harsh realities of the Vietnam War’s unsettling aftermath, the (now almost seemingly quaint) Watergate scandal, and a faltering economy. Young people faced unemployment, rising costs of living, and a sense of betrayal by political institutions. At the same time, ongoing post-World War II suburbanization and the continued decline of industrial cities created feelings of confinement and a longing for something more. Born to Run speaks directly to these conditions. Its characters – dreamers, outcasts, and lovers – grapple with dead-end towns, uncertain futures, and the yearning to break free. Songs like “Backstreets” embody this sense of disillusionment with lyrics like:

At night sometimes it seemed you could hear the whole damn city crying

Blame it on the lies that killed us, blame it on the truth that ran us down

The album’s title track, “Born to Run,” however, is perhaps the clearest expression of this sentiment. With its anthemic sound and desperate lyrics, it channels the urgency of young people seeking liberation from economic and social stagnation with lyrics like:

Oh, baby this town rips the bones from your back

It’s a death trap, it’s a suicide rap

We gotta get out while we’re young

Springsteen’s protagonist and his companion Wendy dream of running away from a world that feels limiting and oppressive, echoing the broader national mood of restlessness. This reflects the historical reality of a generation caught between fading ideals of the 1960s and the pragmatic challenges of adulthood in the 1970s.

The album’s urban imagery is another reflection of its time. Songs such as “Jungleland” depict gritty cityscapes filled with violence, betrayal, and fleeting moments of beauty, with lyrics like:

In the tunnels uptown

The Rat’s own dream guns him down

As shots echo down them hallways in the night

No one watches when the ambulance pulls away

Or as the girl shuts out the bedroom light

Outside the street’s on fire

In a real death waltz

Between what’s flesh and what’s fantasy

And the poets down here

Don’t write nothing at all

They just stand back and let it all be

And in the quick of the night

They reach for their moment

And try to make an honest stand

But they wind up wounded

Not even dead

Tonight in Jungleland

These depictions mirrored the state of many American cities in the 1970s, which were experiencing economic decline, rising crime, and social unrest. Yet, even amid this bleakness, Springsteen’s music found hope in resilience and solidarity, echoing the determination of communities struggling through hard times.

Born to Run also reflects the cultural fascination with mobility and the open road, a theme long central to American identity. Songs such as “Thunder Road” embody how in the 1970s cars symbolized both freedom and escape, especially for working-class men. Consider lyrics like:

Well, I got this guitar, and I learned how to make it talk

And my car’s out back if you’re ready to take that long walk

From your front porch to my front seat

The door’s open, but the ride it ain’t free

And I know you’re lonely for words that I ain’t spoken

But tonight we’ll be free, all the promises’ll be broken

Springsteen’s characters often drive toward uncertain destinations, embodying the restlessness of a generation searching for meaning in a changing world. [See Dr. Katherine Parkin, “The Key to the Universe: Springsteen, Masculinity, and the Car,” in Bruce Springsteen and the American Soul: Essays on the Songs and Influence of a Cultural Icon (2011).]

Ultimately, even a history nerd like me can admit that Born to Run endures because the music is just so good. And yet, if we dig just a bit below the surface, we can see how the album successfully distilled the spirit of its historical moment into this music that feels so timeless. It captured the anxieties of a post-Vietnam, post-Watergate, stagflation-era America while also offering the possibility of fulfillment through dreams, love, and resilience. In this way, the album stands as both a product of its time and a lasting reflection on the struggles and aspirations of ordinary Americans – of the 1970s, and today.

A Lasting Cultural Impact

When Bruce Springsteen released Born to Run in August 1975, he could not have known that the album would come to define not only his career but also document a pivotal moment in American history. Fifty years later, the record remains a touchstone in rock and roll, widely recognized for its sweeping ambition, emotional honesty, and enduring influence. Its historical legacy lies not only in the way it secured Springsteen’s place as one of the greatest American songwriters, but also in how it came to document a generation’s dreams, anxieties, and sense of possibility. [See Louis P. Masur’s Runaway Dream: Born to Run and Bruce Springsteen’s American Vision (2010).]

Today, Born to Run is preserved in the Library of Congress’s National Recording Registry as a culturally significant work, a testament to its lasting value. The album is more than a rock milestone; it is a cultural landmark and a history lesson.

Melissa Ziobro

Director of Curatorial Affairs

Bruce Springsteen Archives & Center for American Music

Monmouth University

September 2, 2025